Key phrases: "Rwandan radio program designed to challenge norms of deference, legitimize expressions of dissent, and encourage local problem solving and dispute resolution" led to "Our results indicate that although the program did little or nothing to change many domains of individual belief and attitude, it effected profound changes in behavior. Radio listeners in the treatment group became more likely to express dissent with peers and less likely to defer to local officials when solving local problems. These changes were balanced by an increased sense of collective responsibility and local initiative."

This is important stuff. So little effort is put into effective interventions that lead to moral action - here, stopping genocide.

Political scientists Christian Davenport and Allen Stam provide an unconventional — and thus controversial — answer to the first question. They discuss this research in the most recent Miller-McCune Magazine. (The project’s website is here.) A few excerpts from the article:

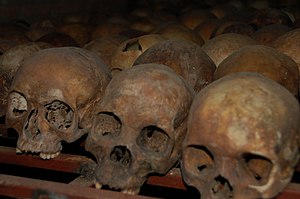

In the end, our best estimate of who died during the 1994 massacre was, really, an educated guess based on an estimate of the number of Tutsi in the country at the outset of the war and the number who survived the war. Using a simple method —subtracting the survivors from the number of Tutsi residents at the outset of the violence — we arrived at an estimated total of somewhere between 300,000 and 500,000 Tutsi victims. If we believe the estimate of close to 1 million total civilian deaths in the war and genocide, we are then left with between 500,000 and 700,000 Hutu deaths, and a best guess that the majority of victims were in fact Hutu, not Tutsi…

One fact is now becoming increasingly well understood: During the genocide and civil war that took place in Rwanda in 1994, multiple processes of violence took place simultaneously. Clearly there was a genocidal campaign, directed to some degree by the Hutu government…At the same time, a civil war raged — a war that began in 1990, if the focus is on only the most recent and intense violence, but had roots that extend all the way back to the 1950s. Clearly, there was also random, wanton violence associated with the breakdown of order during the civil war. There’s also no question that large-scale retribution killings took place throughout the country — retribution killings by Hutu of Tutsi, and vice versa.Mitigating the after-effects of this conflict is the subject of a new article in the American Political Science Review by Elizabeth Levy Paluck and Don Green. Their jumping-off point is the notion that a “political culture” of deference to authority and conformity helps produce genocide. They seek to determine what can mitigate such a culture by encouraging the expression of dissent and collection problem-solving. They randomly exposed rural Rwandans to a radio program that encouraged these behaviors, and other Rwandans to a program about health. What did they find?

"

Our results indicate that although the program did little or nothing to change many domains of individual belief and attitude, it effected profound changes in behavior. Radio listeners in the treatment group became more likely to express dissent with peers and less likely to defer to local officials when solving local problems. These changes were balanced by an increased sense of collective responsibility and local initiative. Our findings suggest that certain aspects of political culture are susceptible to short-term change in the wake of noninstitutional interventions, such as media programs. Evidently, the mass media can influence the set of culturally available behavioral practices that citizens use—the “toolkit” of political cultural conduct.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=736a5c6c-662b-4a8b-93fc-6b9f7fa61557)

No comments:

Post a Comment